With my first four witnesses now off the stand, we turn to the main orthopedic witnesses:

With my first four witnesses now off the stand, we turn to the main orthopedic witnesses:

Thursday, June 19th. Arrive at court for 11:30 charge conference. Bad news. Yanks are playing a day game. I park in my usual lot 50 yards from the ball yard. I have no doubt the game will end when court does. My two trial bags on the wheelie are now accompanied by two exhibit bags slung over my shoulder for a medical illustration and a model of the spine, pelvis and hips.

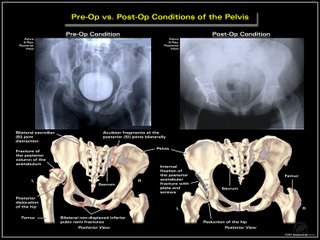

The plaintiff’s treating orthopedist takes the stand. He’s seen her about 20 times. He’s my last witness. Out come the spine and the medical illustration that I commissioned from Anatomical Justice, shown here, displaying the before and after of plaintiff’s hip surgery. The doctor comes down off the witness stand for an anatomy lesson and tells the jury what happened to his patient’s body. I disappear into a place behind the jury and ask him to explain what the heck all those bones are, what happened in this accident, how the woman was put back together, and what her future holds. Nothing resembling legalese crosses my lips.

In a proper direct exam, the lawyer should barely be noticed. The entire focus must be on the witness. My cross exam style is, of course, quite different. A proper cross has the lawyer “testifying” and the witness simply agreeing, or disagreeing. Unless, of course, one decides to break those rules. Which I might do tomorrow for defendant’s orthopedist.

Defense tries in cross-exam to claim that her back injuries are pre-existing by using records from several years back. Their problem is that their own experts don’t agree in their reports that any of her complaints were pre-existing. They can’t. Those records were never given to them.

My case is now in. I relax a bit. Maybe I’ll even eat. Maybe.

I head back down the hill to the parking lot. The streets are filled with blue Yankee shirts. The strains of Sinatra singing New York, New York wafts out of the stadium, filling the Bronx air. The game has just ended. The 20-minute drive home will take an hour.

Friday, June 20th. We have only one witness again today, a defense orthopedist. His report discusses only the medical records from 2005 and his examination in March of 2008. He has not seen any pre-accident records. He has not seen any films from 2006 or 2007 regarding the plaintiff’s post traumatic arthritis of the hip. He has not seen the records of her current treating orthopedist for the past two years. Testimony should be quick. I do not anticipate the need to impeach him (too much), since he hasn’t seen the important records.

But it won’t be easy. Because there he is, standing in the courtroom by one of the big picture windows looking at films he has never seen before. Or rendered an opinion on before.

The jury comes in and he takes the stand and he starts to talk about all the records and x-rays that were not included in his report. I object. The judge lets him go anyway saying he can discuss things that are in evidence. It is now trial by ambush. There is no report to work from. There is no deposition of him (not permitted of experts in New York). And no way to know what will come out of his mouth. The jury can see my evident displeasure.

The defense has been created during trial. I will comment on this in summation. (The reader would do well to note here, however, that neither of the defense trial attorneys were responsible for the day-to-day work-up of the case. These postings are intended to give the day-to-day flavor of what a trial is about and the types of decisions that need to be made, not criticize opposing counsel, who were both quite experienced and able.)

The doctor testifies, contrary to her treating physician, that based on the films he saw by the big picture window that very morning that there is no post-traumatic arthritis. He says that, contrary to her treating physician, that a hip replacement will not be needed in the future. I need to modify my cross-exam.

I start by using him as my own expert. I’ll get some good stuff first before I impeach him. I pick up the skeletal model and, while I stand directly in front of him and the jury, walk him through the shattering of the acetabulum — that’s the socket part of the hip’s ball-and-socket joint — in the accident when the femur was rammed through it. With my hands on the model I pull the femur out of the socket and push it back to the place it was dislocated and ask him if he agrees on the mechanism of injury, and the risks ahead due to this trauma. I walk him through the two reductions of the dislocation and the repair of the fracture and the risks of post-traumatic arthritis. He asks for the spine I am holding and I assent to let him use it, contrary to common cross-examination principles. I’m breaking a rule because I am, at this point, using him as my own expert to describe the uncontested initial trauma.

I stop lobbing softballs to the witness about the nature of her initial trauma and surgery when it comes time to discuss her current condition. I cross him on the fact that the opinion of “moderate disability” that he gave in his report — that he now claimed in court was based in part on pre-existing issues — couldn’t possibly have been the basis of his opinion since he hadn’t seen those records when he wrote his report. He is forced to modify his opinion and claim that he was only talking in the abstract and not about this patient. I don’t think the jury is fooled, but I won’t know until the verdict.

I force him to concede she has current disability due to the hip fracture, that she can’t do her job because of it, and force him to concede she is limited in her ability to do household chores.

A courtroom observer, impartial, tells me that cross went well. Unfortunately, she isn’t on my jury.

I go to sleep with a notepad by my bed for the bazillion thoughts that are running though my mind about the trial.

Query: Do hourly lawyers get to bill for the time that they obsess and think and strategize about a trial when they are home with the family?

Next Up: Two additional defense witnesses. Stay tuned.

———————————————————–

Addendum — The full series of posts:

Synopsis of the case at my firm’s website

-

- .

Pingback: Trial Blog, Part 1 (Bronx Trial Assignment Part) – New York Personal Injury Law Blog

Pingback: Trial Blog, Part 2 (Jury Selection Starts) – New York Personal Injury Law Blog