Michigan attorney Steven Gursten

Wow. Defense-medical exams and a defamation claim against a law blogger! Two of my favorite topics wrapped up in one ugly Michigan incident now ongoing.

Now you folks know I have a thing or two to say about doctors that do a lot of defense medical-legal exams. And you know I have a thing or two to say about BS claims of defamation, having been on the receiving end of a couple of moronic lawsuits.

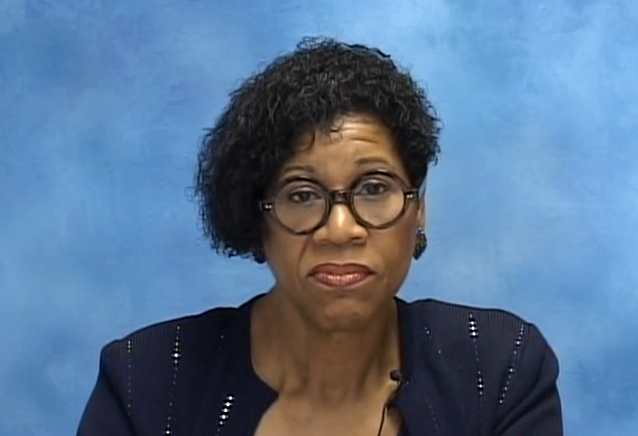

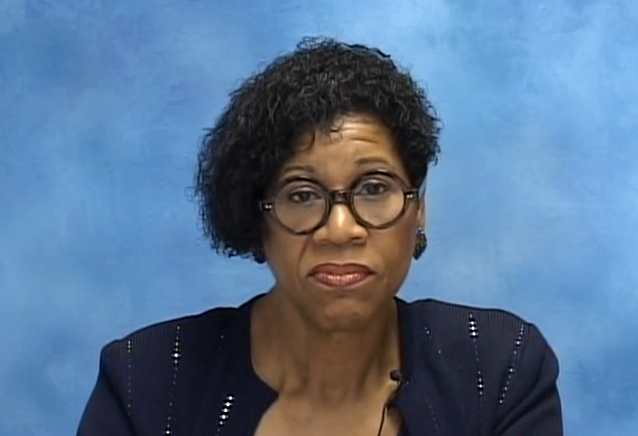

Now comes before us today one Dr. Rosalind Griffin, a Michigan psychiatrist, with a different tactic: Filing a grievance against lawyer Steven Gursten for blogging about a medical-legal exam that she did on one of his clients.

Gursten was so ticked off at Dr. Griffin, that he wrote about her. Like me, he thinks that many of the doctors that make these exams a staple of their practices are doing hatchet jobs on the injured plaintiffs in order to benefit the insurance companies.

(For a comic view of how one lawyer sees it, you can view this cartoon.)

The short version of today’s story is that Gursten’s client was hit by two trucks, and he asserts that the client suffered a traumatic brain injury, broken back, and other significant injuries. Dr. Griffen then did the defense medical exam (DME) — sometimes improperly called an independent medical exam (IME) — and issued a report.

Gursten then presented evidence and asked readers to draw their own conclusions as to whether Dr. Griffen committed perjury. In fact, by the title of his posting, you can see that this invitation to readers was his explicit intention:

Heading: IME abuse? Read the transcript of Dr. Rosalind Griffin in a terrible truck accident case and decide for yourself

Subheading: How many thousands of innocent and seriously hurt people lose everything because of so-called “independent medical exams,” such as this example by Michigan psychiatrist Dr. Rosalind Griffin?

Dr. Rosalind Griffen

He presented evidence that Dr. Griffen — who he said is “a rather notorious IME doctor here in Michigan” — was less than candid in her assessment.

Gursten asserts that this evidence disproves the doctor’s claim that the client said during the exam that his condition was improving, that the client had minor medical conditions, and despite “a closed-head injury, traumatic brain injury, abnormal memory and concentration, PTSD and a badly fractured and collapsed T12 vertebral body, as well as fractures to his mouth, shoulder and knee” that the client’s chronic pain actually came from a 30-year-old whiplash that had been asymptomatic.

This presentation of evidence, and request that readers make their own determination as to whether Dr. Griffen committed perjury, occurred Nov. 13, 2014.

Thirteen months later, Dr. Griffen filed a grievance, claiming defamation, and asking that the Committee require the lawyer to:

- “delete his outrageous posting”; and

- “[R]emove the link to Google results for my name.” [I didn’t make that up, I swear. — ET]

- Punish and sanction him for putting her testimony and her conduct under oath on the internet for people to read.

Gursten wasn’t cowed by the complaint and proceeded to put it up online this week in a new posting with this heading and subheading:

Heading: Sticks and stones and…attorney disbarment? Will the First Amendment lose out when IME doctor files grievance to conceal her testimony in injury case from the public?

Subheading: IME doctor files grievance to suppress blog post and punish attorney for disclosing her conduct

Over the course of a very extensive follow-up posting this week, he provided many examples of differences between what the doctor claimed, and what he said actually happened. This is a sample, with much more at the original posting:

| What Dr. Griffin claims James Fairley said. |

What James Fairley actually said. |

| “[A]ccording to his own statement he feels less depressed and is making progress.” (IME Report, Page 8) |

“Q. What’s a good day for you? A. I don’t know. I haven’t had one lately. … I just have a profound sadness … Q. Do you think you’re depressed, sir? A. I do. … Q. Have you been tearful? A. Oh, yeah. I cry at the drop of a hat sometimes.” (Fairley Dep., Page 58 (lines 1-2, 7), Page 61 (lines 13-14), Page 62 (lines 4-5)) |

In the text of the grievance, Dr. Griffen complains thusly about the original blog post:

Notably, it is the first item returned when someone uses the Google search engine on my name, thereby ensuring that it will be noted and read by individuals researching me or selecting a psychiatrist who will best meet the needs of the patient.

The problem, of course, is that Gursten merely provided the documents and video testimony, and pointed to various sections of them, while offering his opinions. He did what lawyers do: He presented evidence and asked the jury (his readers) to decide.

The doctor’s complaints that calling her “notorious,” or her exam a “hatchet job,” would be merely opinion. And opinion is not actionable under the First Amendment. It isn’t even a close call.

She also tries to make the complaint, unconvincingly I might add, that writing about her exam and testimony violates Rule 8.4 of Michigan’s rules of professional conduct which state that it is attorney misconduct to:

(c) engage in conduct involving dishonesty, fraud, deceit or misrepresentation;

(d) engage in conduct that is prejudicial to the administration of justice;

Since there is nothing dishonest or fraudulent about providing evidence and asking a series of questions about where that evidence leads, I don’t see how she can possibly prevail. Nor is a public discussion of a very serious issue prejudicial to the administration of justice. In fact, a public discussion is beneficial to the administration of justice. I do it here all the time.

Why would Dr. Griffen — who happens to be a member of the very grievance committee to which she is complaining — file this?

Leaving aside the obvious possibility that she may have friends on the committee, the other possibility is that she tried mightily to find an attorney to bring a lawsuit, and that everyone told her “Are you shittin’ me?” though they may have been a tad more blunt. Then a year went by, the statute of limitations expired in Michigan, and she made this complaint feeling she had to do something.

And so she did. And now people out of state, who had never heard of her, are writing about her. Well played, doctor, well played.

(Pro tip: If you need to file a dopey defamation case, you might try Jonathan Sullivan at Ruskin Moscou Faltischek in New York. He’s the guy that brought Dr. Michael Katz’s pointless and doltish suit against me regarding an “IME” and testimony that Katz did. Who knows, maybe he wants to do it again?)

Addendum: More at Public Citizen, a small excerpt below. At the link are also case citations, and a thorough exposition on the chilling effect that permitting such grievances has on free speech.

Griffin’s complaint amounts to a lightweight defamation claim (lightweight because most of the quoted words are either not actually about Griffin or are opinion rather than facts, because Griffin does not spell out any other allegedly defamatory words as Michigan law would require, and because she says nothing about knowledge of falsity or reckless disregard of probable falsity). It is therefore not surprising that Griffin did not file a defamation claim within the one-year statute of limitations. Instead, six days after the statute expired, she chose to file this bare-bones grievance complaint, hoping that paid grievance staff will conduct an investigation for her, and force Gursten to spend his time and money responding to questions from public officials about his opinions about whether and how justice is afforded to accident victims and specifically how Griffin has or has not testified unfairly or unjustly.

In discussing the Michigan’s Grievance Commission, in highly critical terms for allowing this to go forward and requiring a response from Gursten, Public Citizen’s Paul Alan Levy writes:

The Commission staff might well be hoping to exact an apology as Gursten’s price for peace, but at least so far, Gursten is not only not caving in to Griffin’s pressure, but he has called Griffin’s bluff and raised the ante.

Addendum #2: Scott Greenfield weighs in on Rosalind Griffin using a disciplinary complaint because an actual defamation case would fail, and the completely expected reaction (from anyone in the least bit savvy about the internets):

But if the lawyer disciplinary process seems like easy pickin’s to silence blawgers, the flip side is that we’re not particularly inclined to run scared, and we have this tendency not to take kindly to being extorted through the use of the grievance procedure to shut us up.

Has Dr. Rosalind Griffin ever heard of Barbra Streisand? If she thought she had something to twist her face into a frown before, she’s really gonna hate what happens when her effort to use the disciplinary procedure to silence Gursten not only fails, but backfires big time.