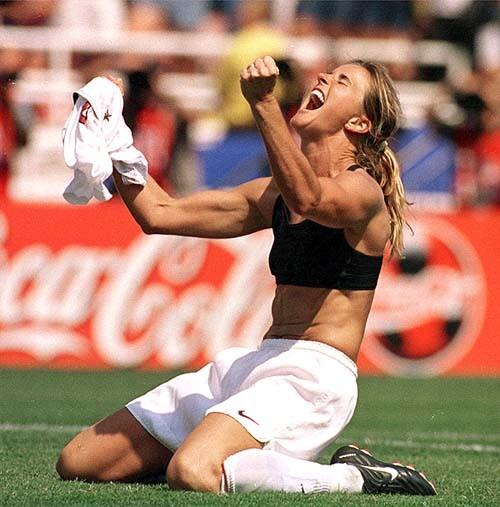

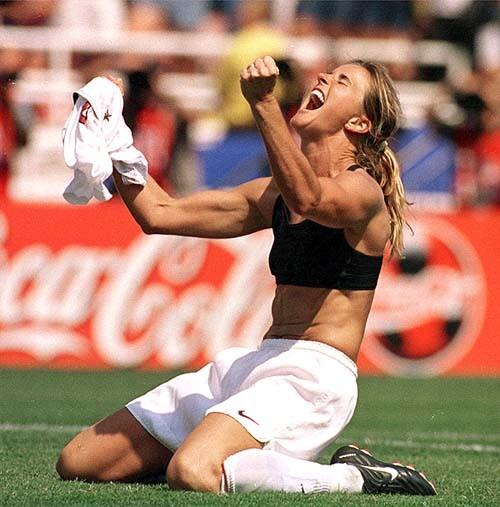

Brandi Chastain after scoring the winning goal in 1999 Women’s World Cup.

As I follow the World Cup with one eye, I stumbled across a letter to the editor in the New York Times sports section, and it left me scratching my head. What the devil was the writer thinking when he sent this in, and why did the NYT bother to publish it?

Since the letter makes an argument, and this is what lawyers do, I wanted to add my two rupees on what not to do when lawyering.

We start on the futbol soccer pitch with the fact that extra time gets added to the standard 90 minutes to account for delays of the game, such as players taking a dive trying to get the ref to call a penalty. As Geoff Foster from the WSJ puts it:

All too often during matches, seemingly fit men fall to the ground in agony. They scream, wince, pound the grass with their fists and gesture to the sidelines for a stretcher. Some of them clutch a limb as if it was just freed from the jaws of a wood chipper.

But after a few moments, just as the priests arrive to administer last rites, they sit up on the gurney, shake it off, rise to their feet and run back on the field to play some more.

Foster does an analysis of the worst offenders of the flopping game, calling the extra minutes “writhing time.” Personally, I prefer “Flop Time.” Your mileage may vary.

And the issue devolves very quickly to this: No one but a ref with a watch really knows exactly how much time is left on the clock. The New York Times wrote about this in: In Time Warp of Soccer, It Ain’t Over Till … Who Knows? Apparently, I wasn’t the only one wondering:

Imagine if an N.F.L. coach never knew when to call for the last-second pass, or an N.B.A. star had to guess when to throw up his desperation half-court shot.

Such situations would be unthinkable in other sports, but vagaries of time are the norm in soccer. Games do not end when a clock expires, but only when the referee decides they are over.

…

Soccer’s elastic definition of time means that no player on the field, no fan in the stands and no announcer on television has any earthly idea as to when the last kick of the ball will come.

(Don’t worry, we’ll get to the lawyering part in a moment. Stay with me here. This time I have a point to make.)

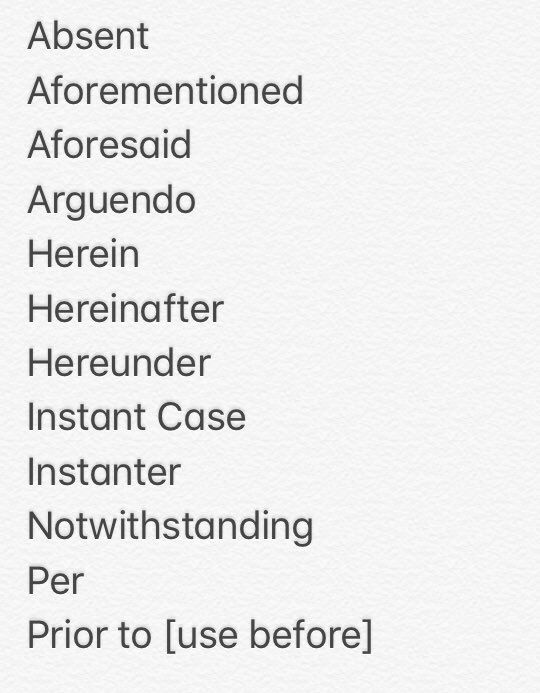

This article didn’t sit well with Thomas Jandl of Washington, who wrote in to the Times in a letter published in yesterday’s sports section. This was the guts of the short letter, with its logical inconsistency:

In baseball, football and even the more free-flowing basketball, coaches prepare and then call certain plays. In soccer, the flow of the game is unpredictable. Players make split-second decisions about their runs, passes, shots or tackles at virtually every moment. As a result, using a stopwatch to determine how much time was wasted or when exactly a game should end makes no sense.

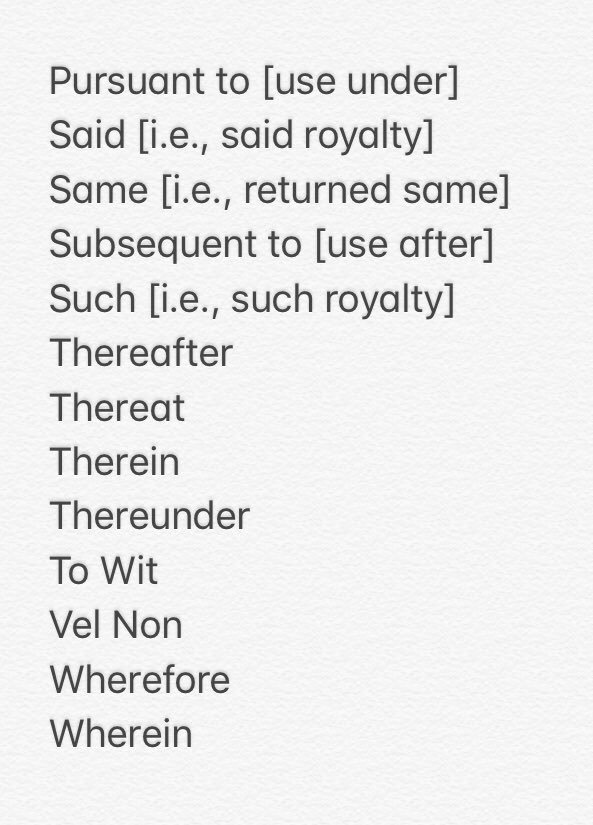

The part about not using a stopwatch –in a game that has a clock — is a complete non-sequitor to comparisons of the game to other sports. It fails the rules of logic. As lawyers, we need logic.

The most common of logical arguments is probably the ancient syllogism. “If this is true, and that is true, then such and such must follow.”

Thus, in a brief, a lawyer might frame the issue with these major and minor premises to lead the court to the obvious answer:

Major premise: According to the statute, the defendant had x days to assert the affirmative defense.

Minor premise: The defendant failed to act within x days on that affirmative defense.

Therefore the affirmative defense was waived.

But that is not what the writer to the NYT did, which is why it’s worth analyzing. He produced, and the NYT printed, the non-sequitor.

The letter instead, has these concepts:

Major premise: Soccer has a clock with 90 minutes plus extra time.

Minor premise: Soccer is wonderful because the flow of the game is unpredictable.

Therefore a stopwatch makes no sense.

If a judge saw this flow of logic from a lawyer, there is an excellent chance the lawyer would lose whatever argument s/he was trying to make. Now I might not be the world’s best writer, but I know enough to try to make logical arguments and avoid those that make me look silly.

The Times gets a gazillion or two letters each day. Why its editors chose something so logically empty is beyond me.

File this under Legal Writing.