When folks read about frivolous or silly legal claims, they invariably ask: What did that person sue for this time? They never seem to ask, what kind of idiotic defense was raised?

Because idiotic defenses don’t make the papers. Until they do.

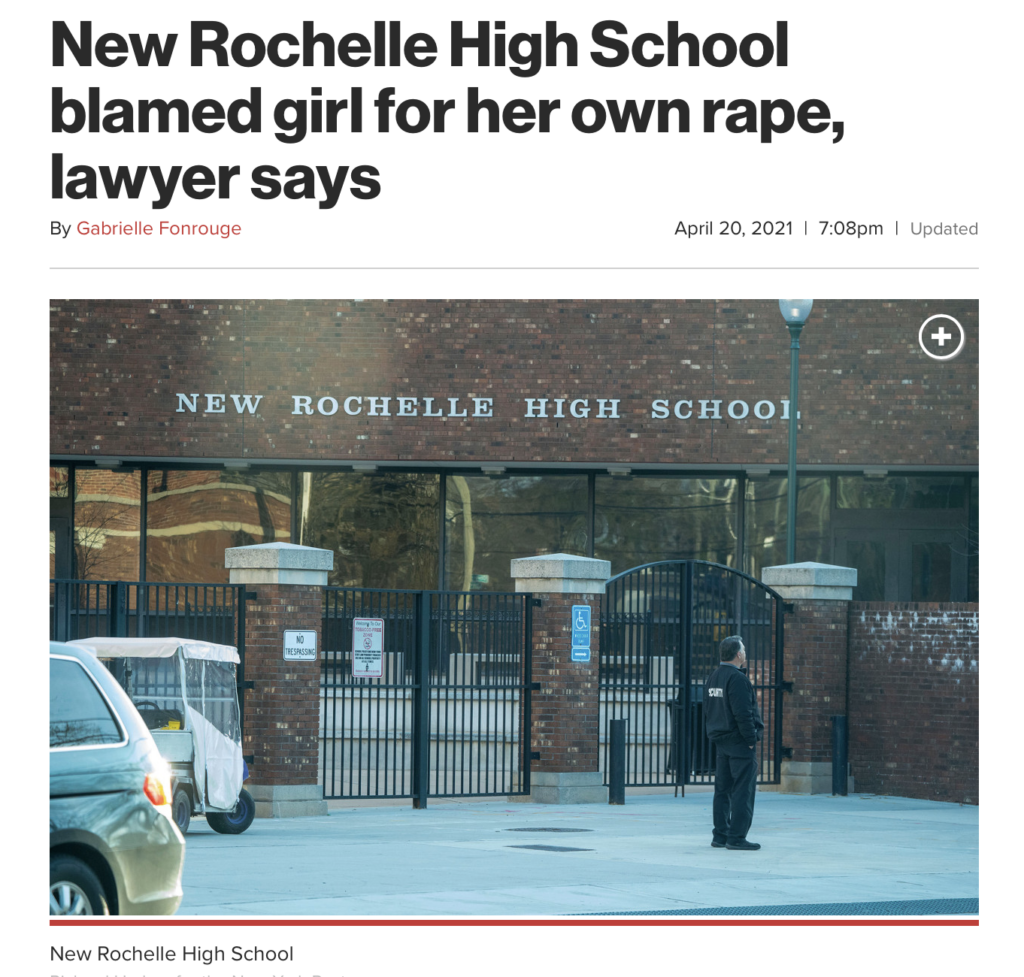

This week the NY Post blared an ugly headline about my hometown high school:

New Rochelle High School blamed girl for her own rape, lawyer says

Blame the victim for her own rape? Is that what the high school did? The high school that my kids just graduated from?

Well, no. That’s what the lawyer did, and the school now pays the price. I know this because I pulled the Answer from the electronic file and saw that there was only a lawyer signature on the verification — no one from the school district.

The Post just pulled this nugget from an affirmative defense raised in that Answer to the suit.

Affirmative defenses, for the non-lawyers who have tuned in, usually are these types in a personal injury case (of which this is one):

- Failing to start suit in a timely manner (statute of limitations);

- Failing to state a claim (fail to make proper allegations that, even if true, would result in the case being tossed out)

- Claiming comparative negligence (the plaintiff was partly at fault and any jury award should be reduced by a proportionate amount — think tripping on a busted sidewalk)

- Assumption of risk (like getting hit by a foul ball at a game – this was a sporting event, the event was a foreseeable risk and the plaintiff is 100% barred from suit)

There are obviously many more in a laundry list of defenses that lawyers pick and choose cut and paste from given the particulars of a case.

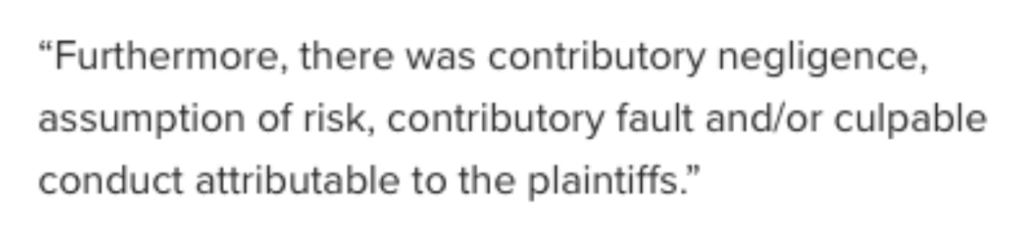

So what did the lawyers claim as affirmative defenses on behalf of the high school? Just that the victim was at fault:

Now that was just dumb. Someone went through the laundry list of potential claims and said the rape victim was at fault for an assault?

And you know this was a mindless cut and paste because “assumption of risk” was also tossed in. But when New York created a comparative negligence statute (CPLR 1411), it wiped out the concept of assumption of risk as an absolute bar to recovery except for the limited cases of sporting events. (See Trupia v. Lake George Central School District). It wouldn’t apply here in any context.

(The actual facts of the incident are unknown to me beyond the Post story, and not for discussion here.)

Now I know what some folks are thinking – what’s the harm of just tossing crap in “just in case”? And the answer is threefold:

First, there’s no actual benefit because pleadings (such as an answer) can be amended, and such amendments shall be freely given. Even up until the time of trial. Even at trial. One of the stock motions at the close of a trial is that “I move to amend the pleadings to conform with the proof.” Sometimes a judge will ask if there is something in particular you have in mind. Sometimes not.

Second, counsel handed the press a headline to the detriment of the client. One thing that must always go through the mind of a lawyer for any public filing: How can the press take this statement and misconstrue it to embarrass my client? And gratuitously blaming someone that says she was raped sure as hell fits that bill.

Third, and possibly the worst. At trial, a savvy plaintiff’s counsel will read the defense and ask the school’s witnesses why they blamed the victim. There is only one answer that can possibly be given: The lawyer did it.

(I did this once when a patient was burned while undergoing surgery: How, dear doctor, was the patient to blame for being burned while she was under anesthesia?)

And when that happens, everything else that lawyer says is looked at sideways by the jury. If the lawyers will blame the victim, why believe anything they say?

This was like kicking the soccer ball into your own goal.